Solutions

Customer Support

Resources

Inside this report, you’ll find what lies ahead for legal leaders in 2026, including how changing work patterns affect wellbeing, where the billable hour is heading, and what’s fueling a rise in in-house confidence.

This report presents the state of in-house in 2026, based on conversations with more than 130 in-house lawyers across sixteen countries in EMEA and the US.

To add depth to the survey findings, we also conducted in-depth interviews with senior in-house lawyers and industry specialists, capturing their perspectives on the results.

The report explores three key themes uncovered in the data this year:

Let’s be honest: nobody enters the legal profession expecting an easy ride.

But for in-house lawyers today, pressure is no longer limited to crunch periods, major deals, or moments of crisis. It’s constant.

The expectation to operate at a consistently high level, often with limited capacity and little margin for error, has become a defining feature of in-house life. And switching off isn’t getting any easier.

The data from this year’s report makes that clear. For many in-house lawyers, sustained pressure and overwork have become the default setting, bringing with them a growing risk of burnout that’s hard to ignore, and harder to escape.

Let’s unpack what’s really driving that reality.

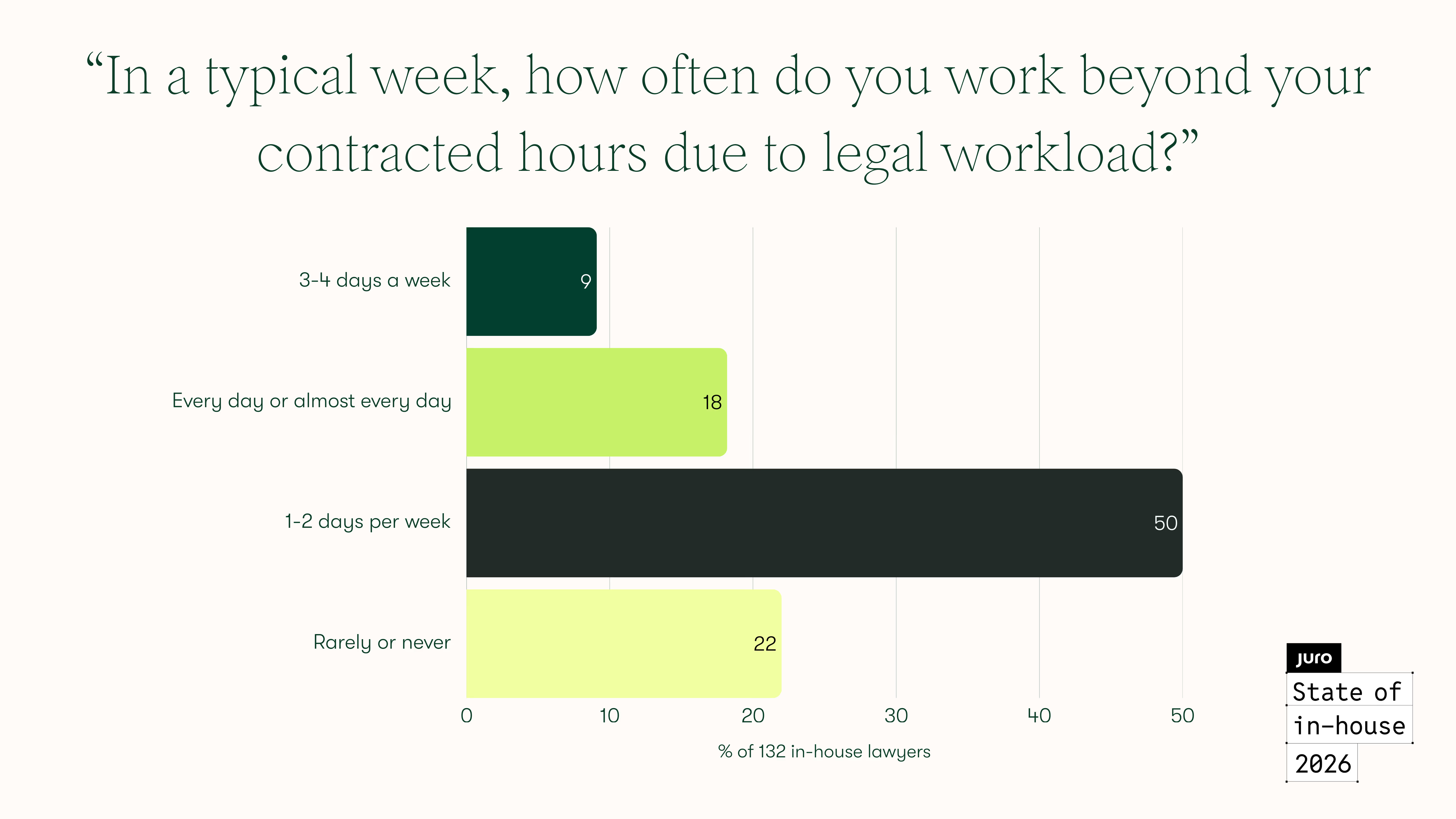

Our survey revealed that legal work is regularly spilling beyond the working day for most in-house lawyers, and often well beyond it. Evenings, weekends, and time off have simply become extensions of the working week.

More than three quarters (77%) of respondents say they regularly work beyond their contracted hours. For nearly one in five, this is not the result of an occasional spike or a difficult period. 18% report working beyond their contracted hours due to workload every day or almost every day.

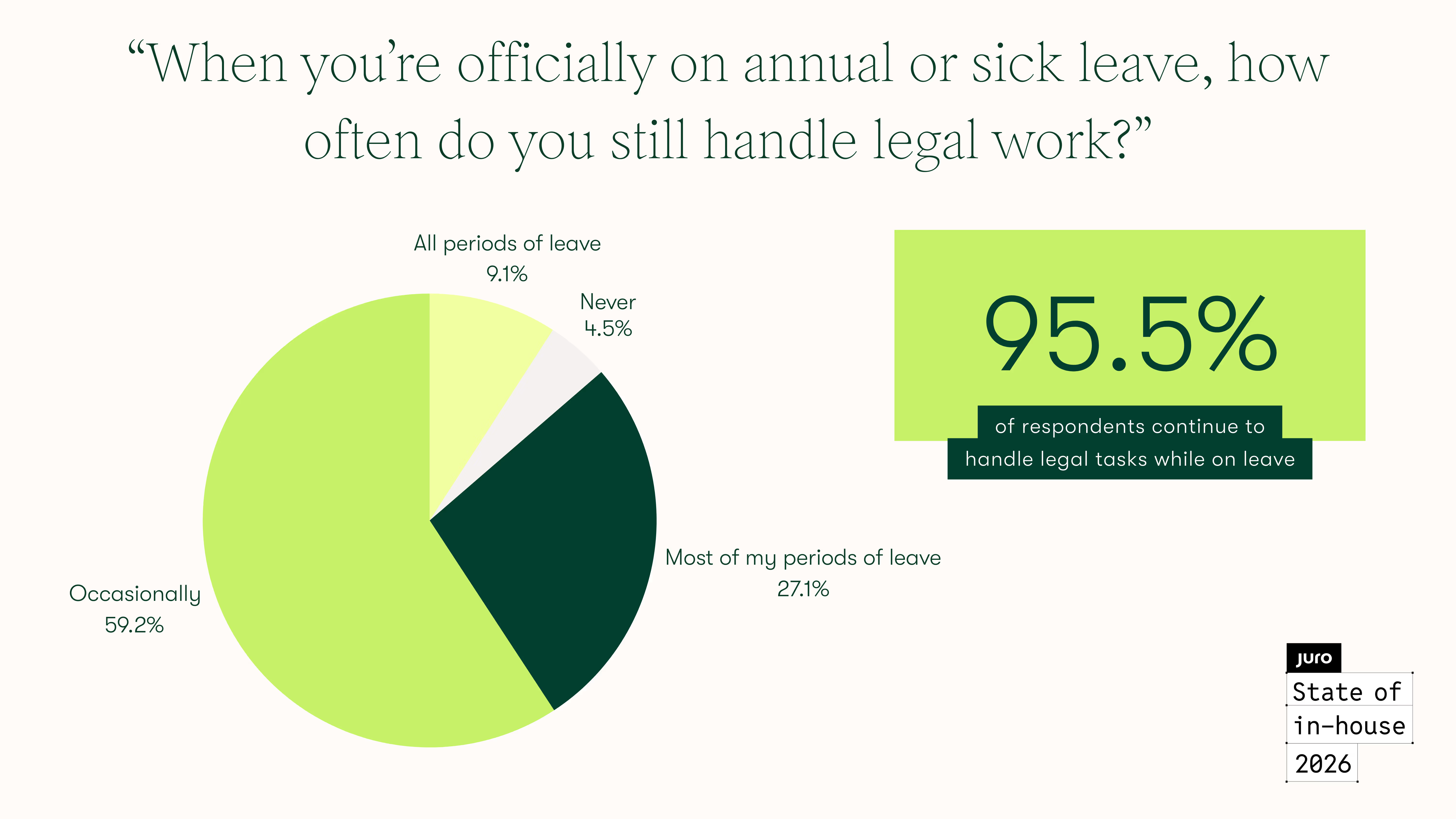

Time off offers little relief from this. Almost all respondents (95.5%) continue to handle legal tasks while on leave, from monitoring emails to stepping in on urgent reviews. For more than a third (36%), this happens during most or all leave periods.

Rebecca McKenzie, Chief Legal & Business Officer at Codat reflects on these findings:

The survey results paint a picture of a profession that is constantly on call, and that sustained availability carries real consequences, with burnout being a common yet often overlooked example.

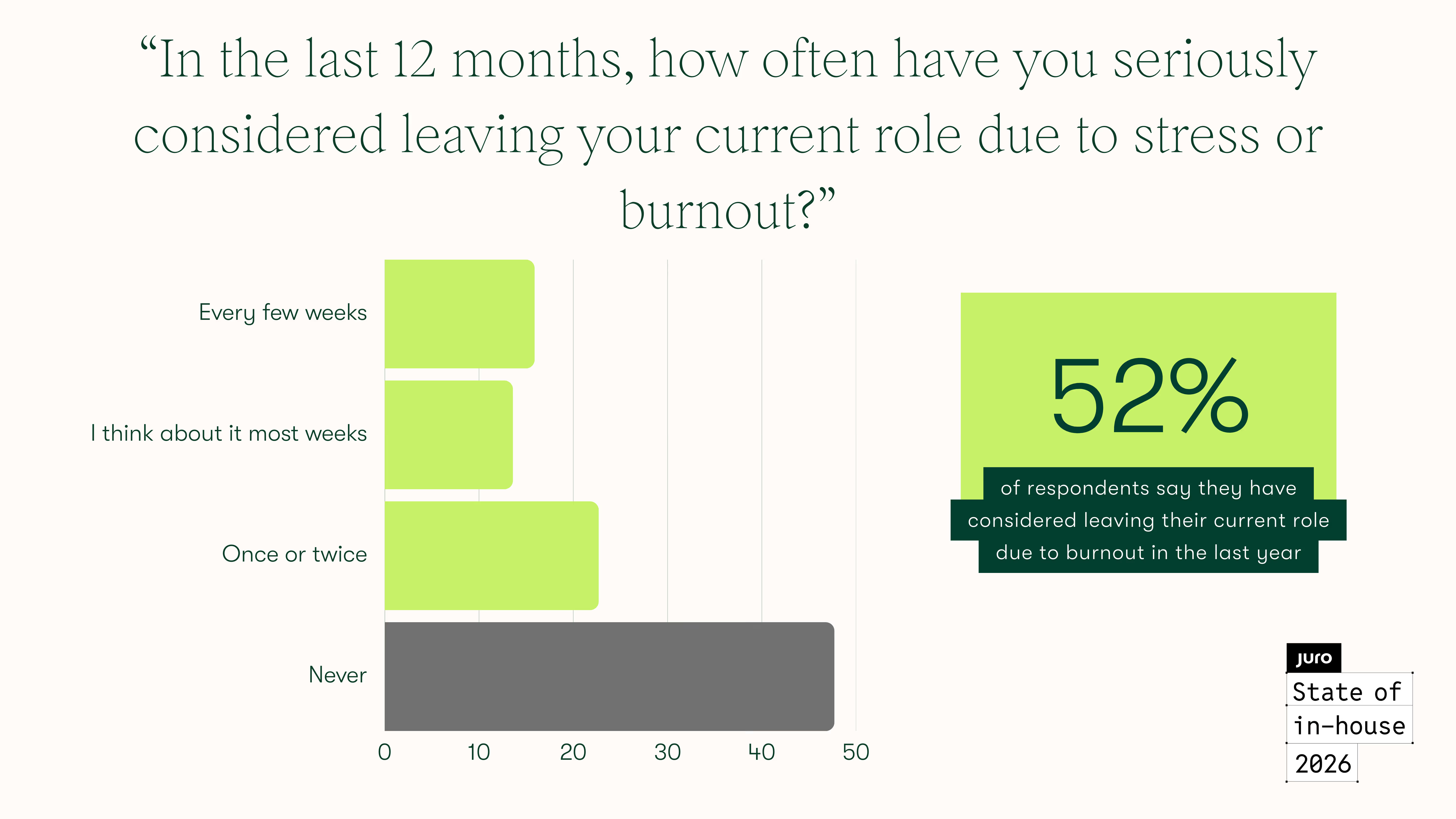

In last year’s survey, almost a quarter of in-house lawyers surveyed reported experiencing burnout in the previous 12 months. This year, that pressure has intensified.

More than half of in-house lawyers surveyed (52%) say they have seriously considered leaving their role due to stress or burnout. In other words, sustained pressure is leading many lawyers to question whether their role, or in-house legal itself, is sustainable.

Juro’s General Counsel, Michael Haynes, explains why this pattern is so hard to break:

The boundary between working time and personal time has blurred to the point where it is barely visible. For legal leaders, this is having a real and measurable impact on mental health.

That’s what makes our next finding particularly surprising.

Despite long hours, interrupted leave, and rising rates of burnout, morale across in-house legal teams remains broadly positive.

More than half of respondents (55%) describe morale as positive, with a further 11% reporting very positive morale.

At first glance, this appears contradictory. How can morale remain high when overworking has become the norm? How do these high-performers find the energy to remain positive without taking enough time to rest and restore?

The answer appears to lie less in working conditions, and more in how in-house lawyers experience the work itself.

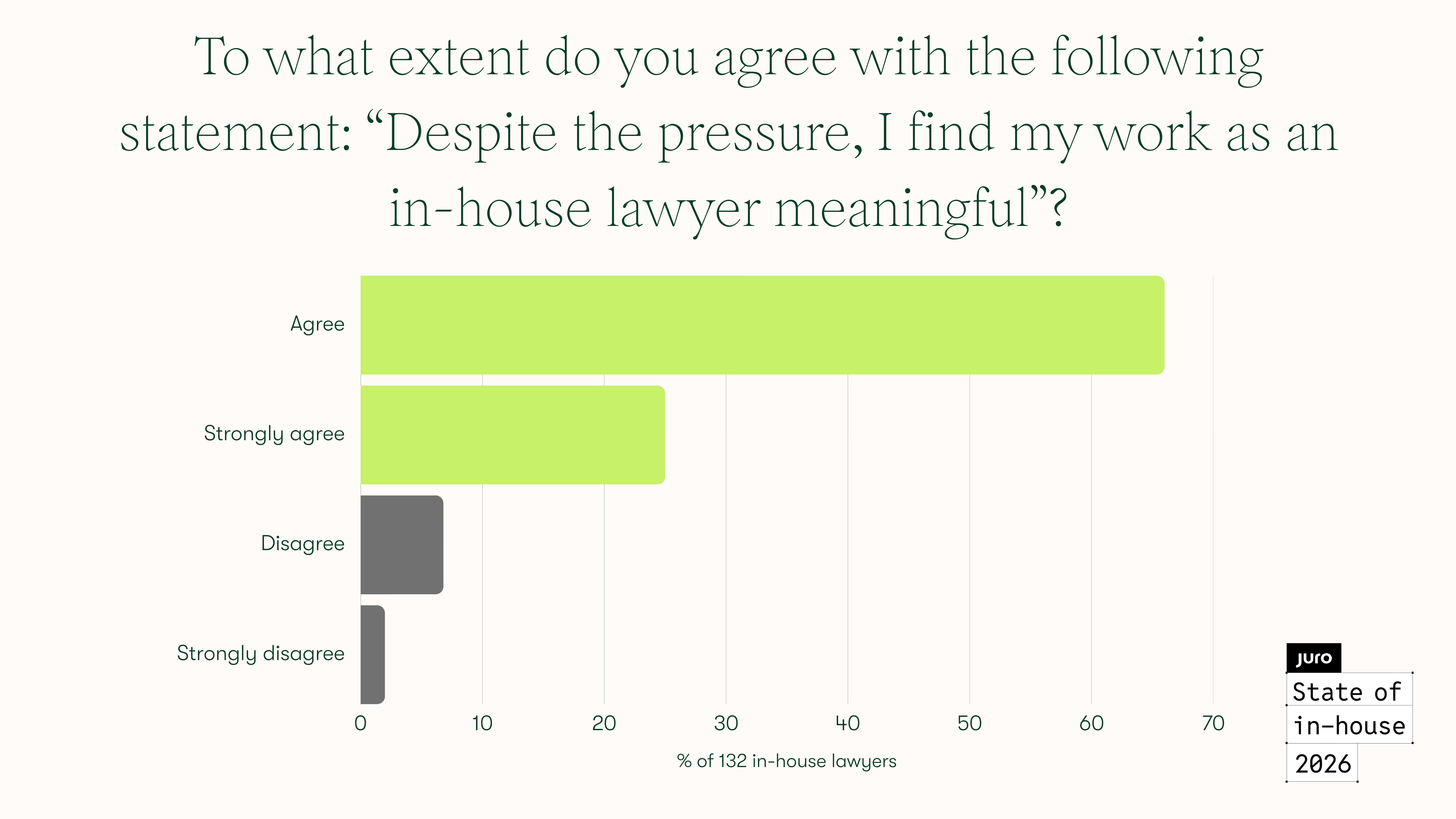

An overwhelming 90% of respondents say they find their work meaningful, even in the context of heavy workloads. One in four feel this very strongly.

This isn’t a story of disengagement. It’s a story of legal teams carrying heavy responsibility, often behind the scenes, because the work genuinely matters to them.

Even as capacity is stretched, in-house lawyers continue to absorb growing workloads, support critical decision-making, and keep their organisations moving, as Rebecca McKenzie from Codat explains:

Nicolette Nowak, General Counsel at Beamery shares a similar perspective:

That commitment is reflected in how lawyers view their career choices. Even with first-hand experience of the pressures involved, 68% say they would choose an in-house legal career again. Just 2% say they definitely would not.

To take this even further, 81% say they are either likely or very likely to recommend an in-house career to a junior lawyer.

For many, the pressure is real. But the work still feels worthwhile.

As Stephanie Dominy, General Counsel & Head of Operations at Tessl, puts it:

To understand what’s driving this pressure, and how in-house leaders plan to navigate the year ahead, we asked our panel of experts what 2026 holds for in-house legal and wellbeing.

Here’s what they said:

Like Nicolette, we remain hopeful that rest and recovery become a greater priority for legal teams in 2026.

As part of that, the wonderful Annmarie Carvalho will join us at Scaleup GC 2026 to deliver an in-person, practical workshop on managing mental health and stress as an in-house lawyer. You can save your place by signing up here.

Now let’s look beyond the in-house team and into the world of private practice.

For decades, the billable hour has survived wave after wave of promised disruption. New technology arrived, productivity improved, and yet the unit of value remained largely untouched.

In 2026, that balance is under real strain.

Large language models are not just accelerating legal work. They are forcing in-house teams to ask a more fundamental question. If the same legal outcome can be delivered faster, should it still cost the same?

AI may not have killed the billable hour. But it has exposed its weakest assumption: that time is still a reliable proxy for value.

The views of the 132 in-house lawyers surveyed for this report suggest that assumption is wearing thin.

Despite the volume of discussion around AI in the legal profession, most in-house lawyers say they have little visibility into how, or even whether, their external firms are using it.

Just 7% of respondents say their law firms have adopted AI tools and have been open about doing so.

By contrast, more than three quarters either believe their firms are using AI without disclosing it (38.6%), or say they have no visibility into AI use at all (38.6%).

For many in-house teams, that lack of transparency matters. If AI is reducing effort and turnaround times, it’s reasonable to expect some reflection of that efficiency in billed hours or fees.

In practice, many in-house lawyers actively support their firms adopting AI. What they are questioning is the transparency around how it’s used, and what that means for value.

So far, those questions remain unanswered.

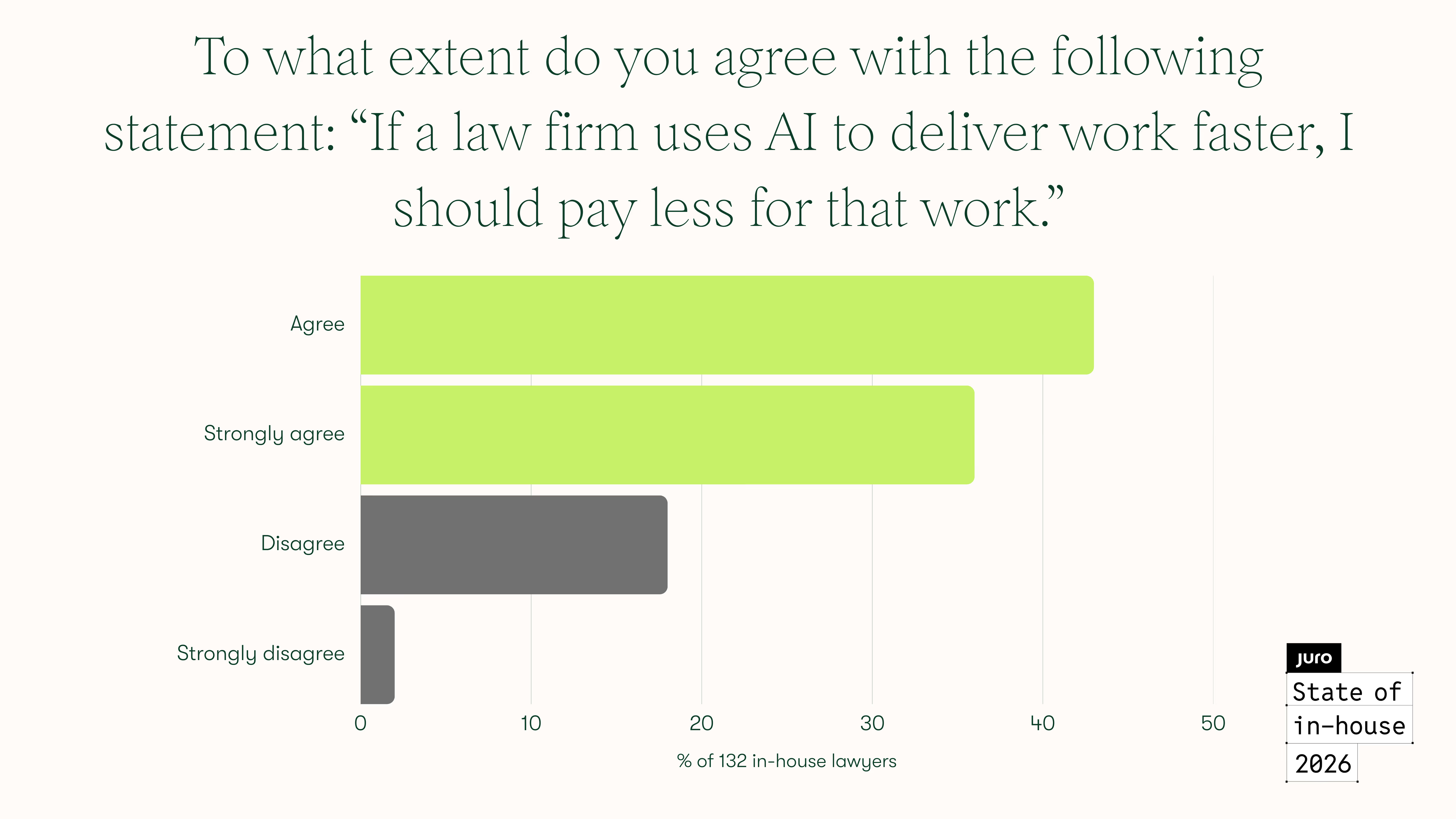

Nearly four in five respondents agree that if a law firm uses AI to deliver work faster, clients should pay less for that work. In practice, that expectation is rarely being met.

84% say they have seen no noticeable reduction in fees or billed hours that they can clearly attribute to AI adoption. A further 11% report that fees have actually increased.

The result is a growing perception that efficiency gains are being absorbed by law firms, rather than shared with clients.

When asked who currently captures the financial benefit of AI within law firms, respondents were unequivocal. 72% believe firms retain all or most of the savings. Just 2% believe those savings are shared between firm and client.

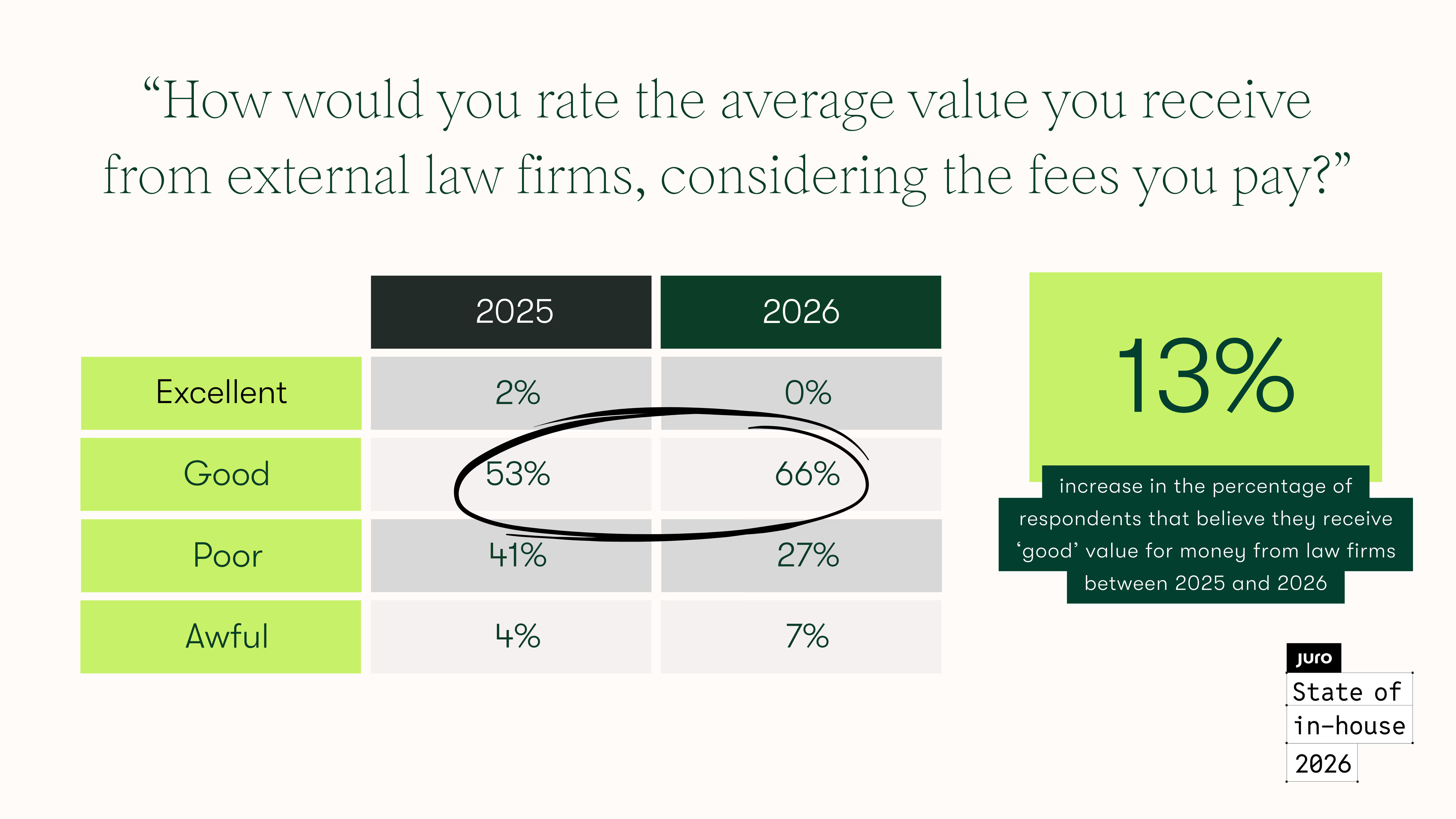

Given what we’ve just seen around AI, pricing, and transparency, one finding stands out.

Compared with last year’s survey, perceived value from external law firms has improved slightly.

Nearly two thirds of respondents (66%) now describe the value they receive as good, up from 53% last year.

At first glance, this feels counterintuitive. Fees are not falling, transparency remains limited, and AI-driven efficiencies are not being shared. And yet, perceptions of value are improving.

Legal leaders we spoke with offered several possible explanations for this shift:

One possible explanation is that law firms are making greater efforts to demonstrate value beyond the specific matters being billed.

As Rebecca McKenzie, Chief Legal & Business Officer at Codat, explains:

While this does not resolve the underlying question around pricing, it may help soften perceptions of cost in the short term.

A second, more structural explanation is that the type of work being sent to law firms is shifting.

As in-house teams adopt AI to automate routine and capacity-driven tasks, the matters that remain with external firms are increasingly specialised, high-risk, or judgement-heavy.

Michael Haynes, General Counsel at Juro, describes this shift clearly:

“The nature of work being outsourced to law firms is changing. I use a simple test: there are only three reasons to outsource legal work.

First, expertise and judgement. This is where a firm offers specialist technical expertise combined with deep knowledge of your business context to answer questions I can’t answer.

Second, capacity. This is work we can do in-house, but we just don’t have enough time nor the volume to justify hiring.

Third, insurance. This is where you know the answer and can do the work, but the risk is existential and you want the comfort and protection that comes with a second opinion. This is typically for “bet the company” issues.

AI is shrinking the second category. By using technology to do work faster and at scale, we no longer need to turn to law firms for capacity. This likely explains why in-house lawyers feel confident taking this work back.”

As capacity-driven work moves back in-house, law firms are increasingly engaged on matters where the stakes, and therefore the perceived value, are higher. In that context, unchanged or even rising fees may feel easier to justify.

There is also a more pragmatic explanation. Many law firms may not yet have realised the financial benefits of AI adoption themselves.

Stephanie Dominy, General Counsel and Head of Operations at Tessl, shares this view:

This perspective is echoed by research from Harvard Law School’s Center on the Legal Profession:

“As the dominance of the billable revenue model continues, it also provides a mechanism to recover investment costs of AI deployment. No firms interviewed plan on recouping AI investments directly from clients.”

For many firms, AI adoption is still in its early stages, with costs and change management coming before meaningful efficiency gains. And it’ll be even longer before these are reflected in your bills.

In-house lawyers are not calling for the wholesale abolition of the billable hour.

What they are asking for is a pricing model that reflects outcomes rather than effort, and recognises that technology has fundamentally changed the cost of delivering legal work.

Traditional hourly billing is risk-averse by design. By tying fees directly to time spent, it protects law firm margins and limits commercial uncertainty. But as AI reduces the input required to deliver many legal outcomes, that model is becoming increasingly difficult to justify.

Michael Haynes, General Counsel at Juro, argues that AI has exposed a long-standing disconnect between cost and value, while also creating an opportunity for firms willing to rethink how they price their work:

“Traditional hourly billing models are risk-averse and defensive. They protect firms’ margins by being directly linked to input costs, but they don’t reflect value for the client. I can count many examples where I’ve received significant value from advice that cost very little because the firm billed by cost, not value.

AI should change that dynamic. It allows firms to deliver the same or better outcomes with far lower input costs. That makes value-based pricing more viable, and potentially more profitable, than ever before.

Firms just need to step outside their comfort zone and take a more entrepreneurial approach to pricing. Some firms are already leading the way, particularly those working closely with scaleups, and they stand to benefit most from AI-driven efficiency as a result.”

For others, AI is simply accelerating a conversation the profession has avoided for years.

As Nicolette Nowak, General Counsel at Beamery, points out, law firms have long benefited from efficiencies without fundamentally changing how that value is shared:

When you dig beyond the data and speak to in-house lawyers, departments are not asking firms to work for less. But they do expect pricing that better reflects outcomes and value delivery in an AI-enabled world.

While that shift continues to play out, forward-thinking legal teams are already reassessing which work genuinely needs to be outsourced, and which can be handled faster, more predictably, and at lower cost in-house.

The next section of this report looks at how in-house legal teams are insourcing and automating work to regain control.

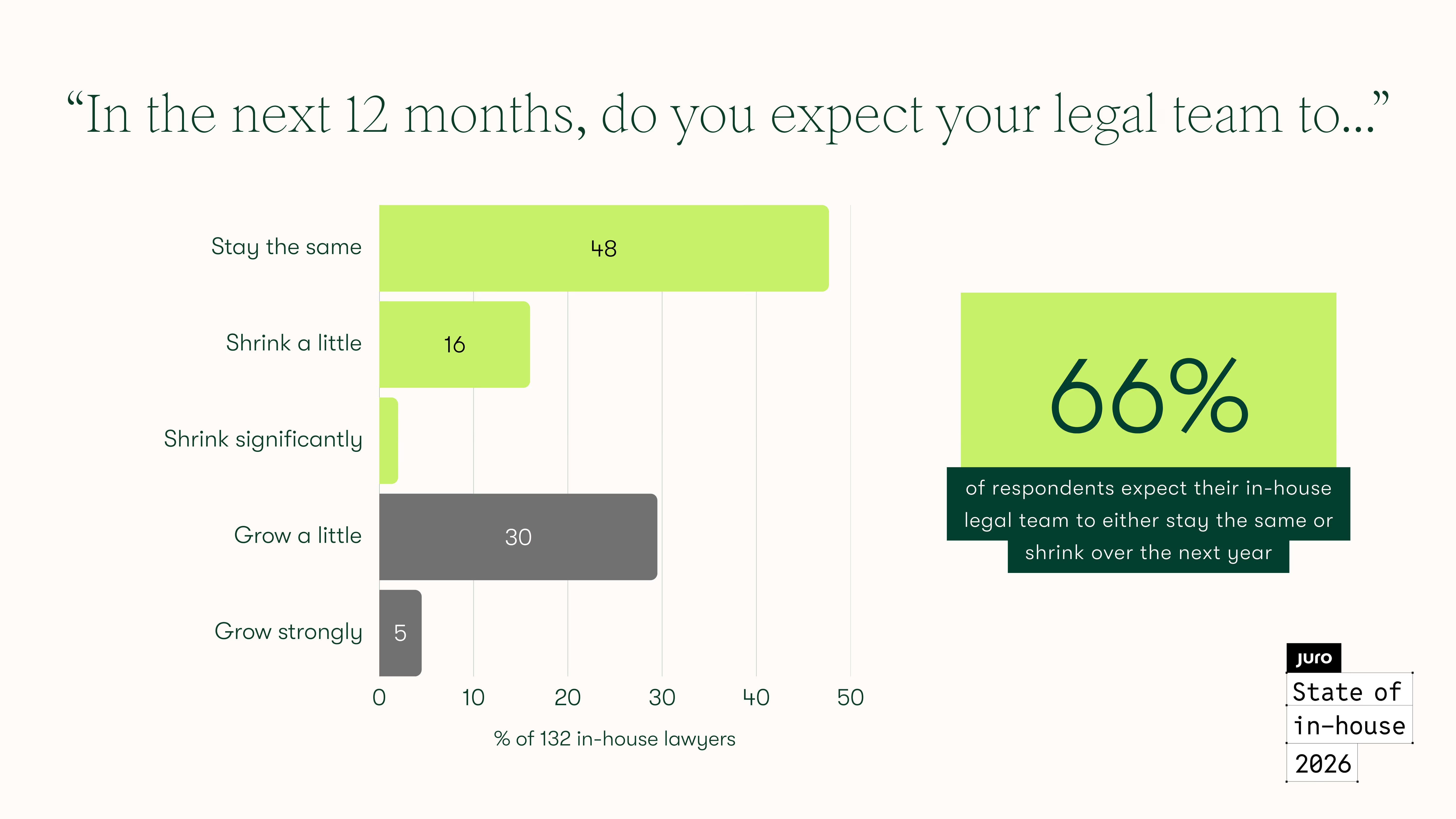

Some things haven’t changed since we surveyed legal leaders last year.

Legal budgets remain under pressure. Headcount growth has slowed, and in many cases stalled entirely. Only a third of in-house lawyers expect their team to grow in 2026. 66% expect their legal team to stay the same size or shrink.

At the same time, demand from the business continues to rise, as reflected in the survey results explored earlier in this report.

But how are in-house legal departments faring in this environment?

Interestingly, many in-house legal teams actually report growing confidence in their ability to manage legal risk internally.

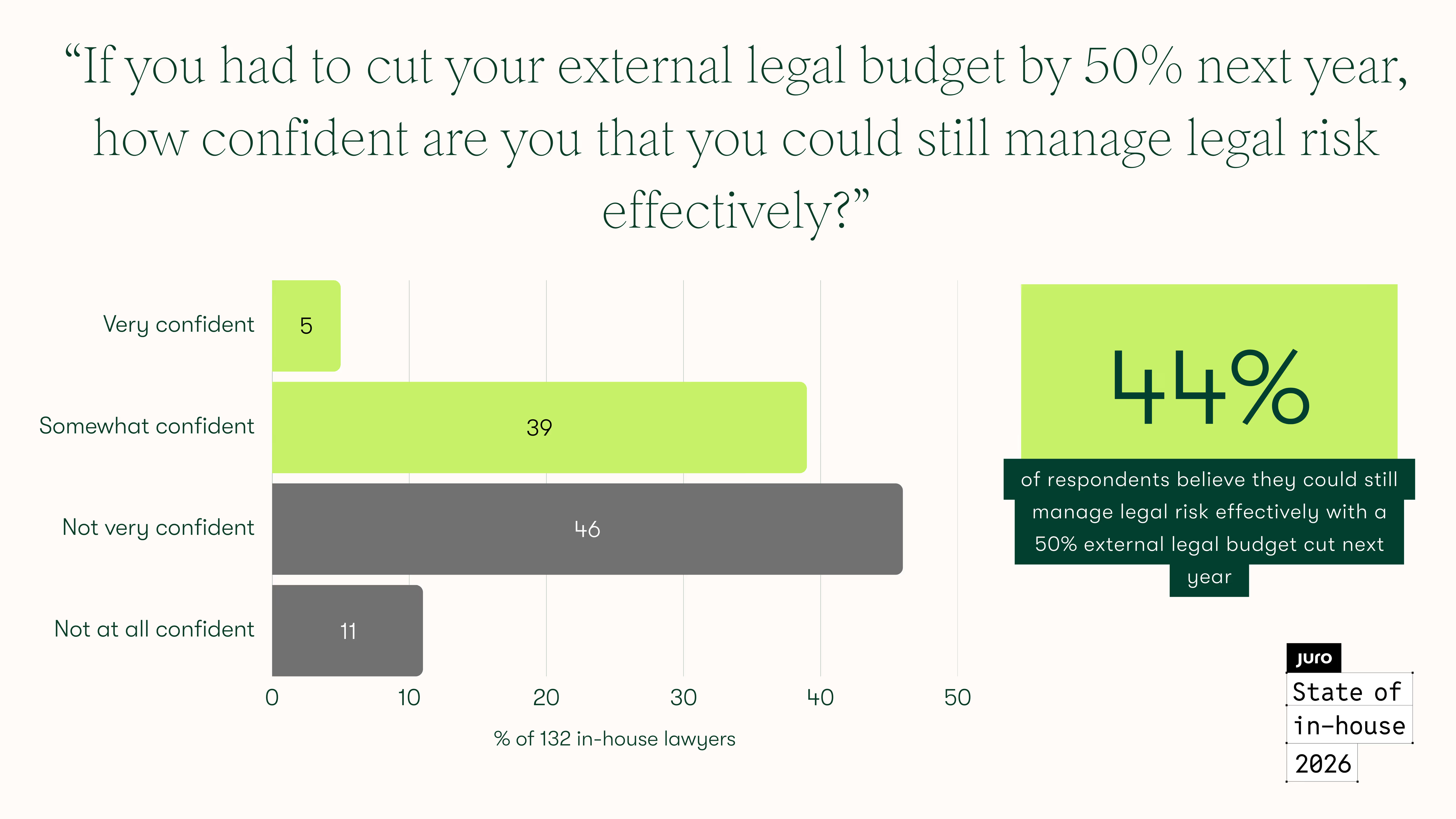

44% of respondents say they would still feel confident or somewhat confident doing so, even with a hypothetical 50% reduction in external legal spend.

On the surface, that confidence might appear counter-intuitive. With tight budgets and limited headcount growth, you might expect legal teams to feel more exposed, not more in control.

But many in-house teams are no longer trying to do the same work in the same way with fewer resources. They are operating with a very different set of tools than they had even a few years ago.

If you cast your mind back to last year’s survey, more than 99% believed AI would change their role within a year, and more than 90% were already using large language models such as Claude or Gemini daily or weekly.

This year’s findings only prove further that AI is taking an even bigger and more meaningful slice of work off lawyers’ plates. In fact, 91% of respondents believe the legal department is as well positioned, or better positioned, than other teams in their business to benefit from AI.

That’s particularly interesting given that legal teams are usually the most cautious function in the business, and the ones responsible for answering the highest-stakes questions.

Looking two years ahead, most respondents believe that at least some of the work they currently send to law firms could be handled in-house using AI tools.

.avif)

This expectation appears to be grounded in experience. Among respondents who have already used AI tools for legal work, 56.8% report a positive or notable impact, with a further 16% describing the impact as very positive.

For many teams, this is no longer theoretical. Insourcing is becoming a practical and proven way to manage workload and control costs, particularly for repeatable, lower-risk work.

Rebecca McKenzie, Chief Legal & Business Officer at Codat has observed this trend firsthand:

At Juro, we speak with in-house legal leaders every day, and nowhere is this shift clearer than in contracting.

Across legal teams, contracts account for a disproportionate share of day-to-day workload. They arrive in predictable formats, follow established playbooks, and create bottlenecks not because of legal complexity, but because of volume.

Review queues build up, minor deviations trigger unnecessary escalation, and lawyers lose time that could be spent on higher-value, more fulfilling work.

This is exactly the kind of work that lends itself to automation.

Juro customers often describe a similar inflection point. Once contracts are standardized, data-driven, and automated with AI, legal teams no longer need to be involved in every step to stay in control. Instead, they define the rules, set the guardrails, and step in only when risk genuinely changes. That frees them up to spend more time acting as strategic partners to the business, rather than gatekeepers to process.

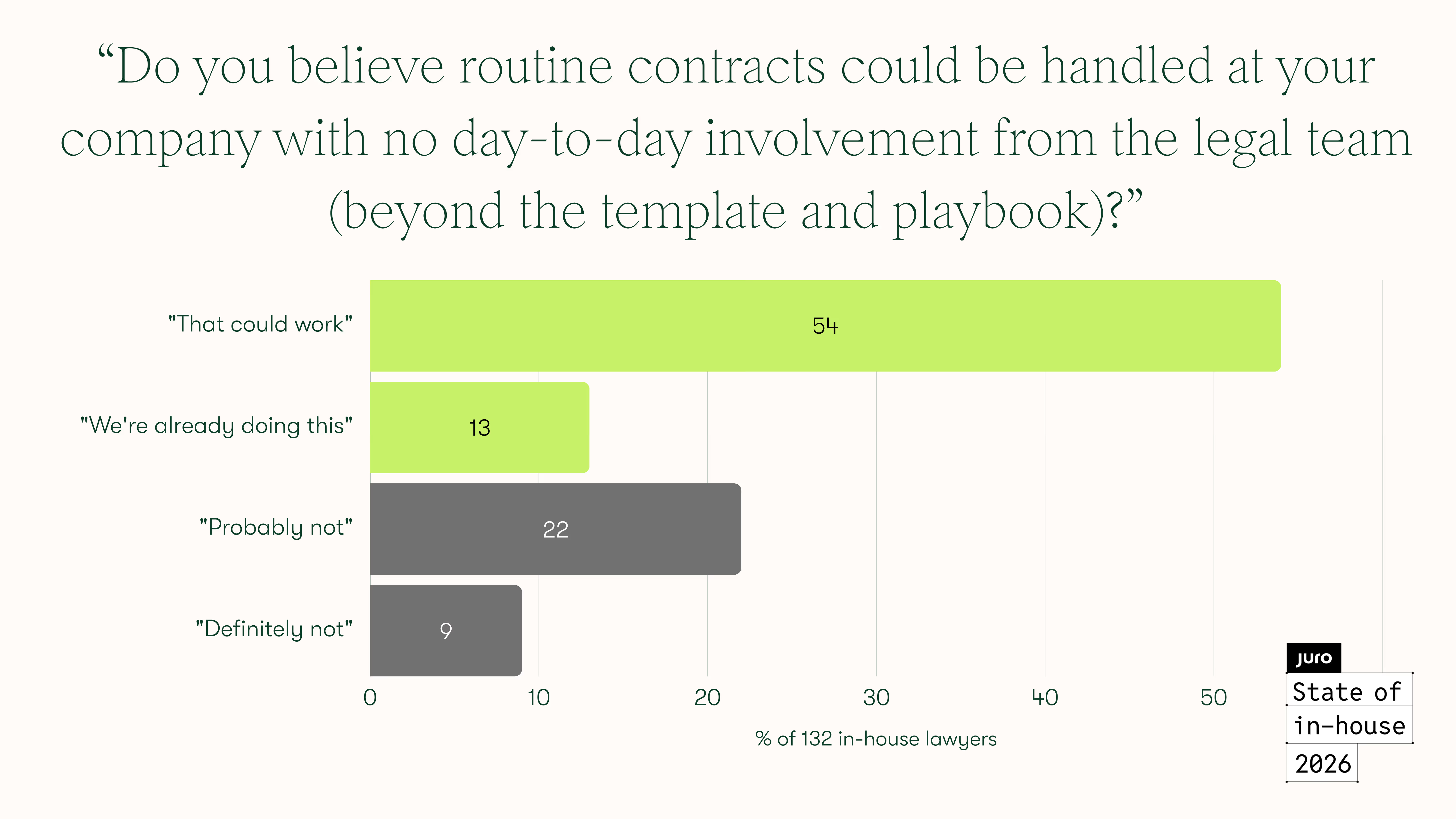

The survey data reflects this shift clearly. When asked whether routine contracts could be handled without day-to-day legal involvement, nearly two thirds of in-house teams said this was either already happening or could realistically work in their organisation:

In other words, nearly two thirds of in-house teams see contract self-service as viable, and many have already put it into practice.

That shift changes how legal teams spend their time, and how the business experiences legal support.

As AI removes low-value, repetitive work from lawyers’ desks, many teams are finally finding the space to operate differently. That shift is unlocking renewed optimism about the future of the profession, and may explain why morale and fulfilment remain high in difficult times.

For Rebecca McKenzie, Chief Legal & Business Officer at Codat, this change is already reshaping what it means to be an in-house lawyer:

In practice, this means that in-house lawyers in 2026 will be valued less for how much work they personally process, and more for how effectively they apply judgement, set direction, and scale legal decision-making across the business.

That shift also changes where lawyers should deliberately focus their skills. As Michael Haynes observes, the biggest gains do not come from simply switching new tools on:

In other words, the lawyers who get the most from AI are the ones who invest time upfront. When workflows are designed properly and legal thinking is built into systems, work moves upstream and confidence grows in self-serve models like contract workflows. That growth allows lawyers to play a very different role in the business, one that is increasingly in demand.

As that role changes, as does what in-house teams look for when hiring.

This evolution is reshaping hiring decisions in 2026. Traditional proxies for seniority, such as years qualified, past firm experience, or what someone did a decade ago, are becoming less reliable predictors of impact, as Stephanie Dominy explains:

For some teams, this means hiring lawyers who are comfortable working with data, systems, and automation. For others, it may mean bringing in legal engineers or operators who can translate legal judgement into scalable processes.

By 2026, the most effective in-house lawyers won’t be defined by how busy they are, or how many contracts they personally touch. They’ll be defined by how well they design legal systems, where they choose to apply their expertise, and how confidently they help the business move forward.

We're looking to a future where technology is no longer just accelerating your work, it's doing it for you while you supervise and orchestrate it.

In most cases, it won’t be the work you did several years ago that shapes your future as a lawyer. It’ll be the work you’re doing now, and the capabilities you’re deliberately building today.

And there's something really exciting about that.